From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article's lead section may not adequately summarize key points of its contents. (August 2012) |

The history of Liverpool can be traced back to 1190 when the place was known as 'Liuerpul', possibly meaning a pool or creek with muddy water. Other origins of the name have been suggested, including 'elverpool', a reference to the large number of eels in the Mersey, but the definitive origin is open to debate and is probably lost to history[citation needed]. It may be that the place appearing as Leyrpole, in a legal record of 1418, refers to Liverpool.[1] There is also the possibility that Liverpool developed from the French word Livrée meaning to trade or dispense with, a word used by The Norman French including King John who granted City Status to Liverpool. This would mean that Liverpool meant Trading Pool or Harbour and could have referred to the early dockside of Liverpool where trading took place even at the time of the City's founding. This would also give the City's Name the same meaning as Copenhagen in Denmark which meaning Shopping Harbour or Trading Harbour.[2][better source needed]

A likely derivation is connected with the Welsh word "Llif" meaning a flood, often used as the proper name for the Atlantic Ocean, whilst "pool" is in general in place names in England derived from the late British or Welsh "Pwll" meaning variously, a pool, an inlet or a pit. In modern Welsh, the name "Lerpwl" is used, based on the English. Another major immigrant group to Liverpool are the Irish, and in Irish the name is "Learpholl". An older Welsh name for Liverpool is "Llynlleifiad", meaning "pool of the floods". The city has had a small Welsh speaking community, mostly migrants from North Wales.

Contents

[hide]Origins[edit]

Although a small motte and bailey castle had earlier been built by the Normans at West Derby, the origins of the city of Liverpool are usually dated from 28 August 1207, when letters patent were issued by King John advertising the establishment of a new borough, "Livpul", and inviting settlers to come and take up holdings there. It is thought that the King wanted a port in the district that was free from the control of the Earl of Chester. Initially it served as a dispatch point for troops sent to Ireland, soon after the building around 1235 of Liverpool Castle, which was removed in 1726.St Nicholas Church was built by 1257, originally as a chapel within the parish of Walton-on-the-Hill.[3]

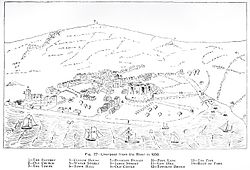

With the formation of a market on the site of the later Town Hall, Liverpool became established as a small fishing and farming community, administered by burgesses and, slightly later, a mayor. There was probably some coastal trade around the Irish Sea, and there were occasional ferries across the Mersey. However, for several centuries it remained a small and relatively unimportant settlement, with a population of no more than 1,000 in the mid 14th century. By the early fifteenth century a period of economic decline set in, and the county gentry increased their power over the town, the Stanley family fortifying their house on Water Street. In the middle of the 16th century the population of Liverpool had fallen to around 600, and the port was regarded as subordinate toChester until the 1650s.

Elizabethan era and the Civil War[edit]

In 1571 the people of Liverpool sent a memorial to Queen Elizabeth, praying relief from a subsidy which they thought themselves unable to bear, wherein they styled themselves "her majesty's poor decayed town of Liverpool." Some time towards the close of this reign, Henry Stanley, 4th Earl of Derby, on his way to the Isle of Man, stayed at his house, the Tower; at which the corporation erected a handsome hall or seat for him in the church, where he honoured them several times with his presence.

By the end of the sixteenth century, the town began to be able to take advantage of economic revival and the silting of the River Dee to win trade, mainly from Chester, to Ireland, the Isle of Man and elsewhere. In 1626, King Charles I gave the town a new and improved charter.[3]

Few remarkable occurrences are recorded of the town in this period, except for the eighteen-day siege of it by Prince Rupert of the Rhine, in the English Civil Wars in 1644. Some traces of this were discovered when the foundation of the Liverpool Infirmary was sunk, particularly the marks of the trenches thrown up by the prince, and some cartouches, etc., left behind by the besiegers.

Transatlantic Trade[edit]

The first cargo from the Americas was recorded in 1648. The development of the town accelerated after the Restoration of 1660, with the growth of trade with America and the West Indies. From that time may be traced the rapid progress of population and commerce, until Liverpool had become the second metropolis of Great Britain. Initially, cloth, coal and salt from Lancashire and Cheshire were exchanged for sugar and tobacco; the town's first sugar refinery was established in 1670.

In 1699 Liverpool was made a parish on its own by Act of Parliament, separate from that of Walton-on-the-Hill, with two parish churches. At the same time it gained separate customs authority from Chester.[3]

Slavery[edit]

On 3 October 1699, the very same year that Liverpool had been granted status as an independent parish, Liverpool's first 'recorded' slave ship, named "Liverpool Merchant", set sail for Africa, arriving in Barbados with a 'cargo' of 220 Africans, returning to Liverpool on 18 September 1700. The following month a second recorded ship, "The Blessing", set sail for the Gold Coast.

The first wet dock in Britain was built in Liverpool and completed in 1715. It was the first commercial enclosed wet dock in the world and was constructed for a capacity of 100 ships. By the close of the 18th century 40% of the world's, and 80% of Britain's Atlantic slave activity was accounted for by slave ships that voyaged from the docks at Liverpool. Liverpool's black community dates from the building of the first dock in 1715 and grew rapidly, reaching a population of 10,000 within five years. This growth led to the opening of the Consulate of the United States in Liverpool in 1790, its first consulate anywhere in the world.

Vast profits from the slave trade transformed Liverpool into one of Britain's foremost important cities. Liverpool became a financial centre, rivalled by Bristol, another slaving port, and beaten only by London. In the peak year of 1799, ships sailing from Liverpool carried over 45,000 slaves from Africa.[3]

Many factors led to the demise of slavery including revolts, piracy, social unrest, and the repercussions of corruption such as slave insurance fraud, e.g. the Zong massacre case in 1783. Slavery in British colonies was finally abolished in 1833 and slave trading was made illegal in 1807 though some slavery apprenticeships ran until 1838.[4] However, many merchants managed to ignore the laws and continued to deal in underground slave trafficking, also underhandedly engaging in financial investments for slaving activities in the Americas.

Industrial revolution and commercial expansion[edit]

The international trade of the city grew, based, as well as on slaves, on a wide range of commodities - including, in particular, cotton, for which the city became the leading world market, supplying the textile mills of Manchester and Lancashire.

During the eighteenth century the town's population grew from some 6,000 to 80,000, and its land and water communications with its hinterland and other northern cities steadily improved. Liverpool was first linked by canal to Manchester in 1721, the St. Helens coalfield in 1755, and Leeds in 1816. In 1830, Liverpool became home to the World's first inter-urban rail link to another city, Manchester, through the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

Liverpool's importance was such that it was home to a number of World firsts, including gaining the World's first fully electrically powered overhead railway, the Liverpool Overhead Railway, which was opened in 1893 and so pre-dated those in both New York and Chicago.

The built-up area grew rapidly from the eighteenth century on. The Bluecoat Hospital for poor children opened in 1718. With the demolition of the castle in 1726, only St Nicholas Church and the historic street plan - with Castle Street as the spine of the original settlement, and Paradise Street following the line of the Pool - remained to reflect the town's mediaeval origins. The Town Hall, with a covered exchange for merchants designed by architect John Wood, was built in 1754, and the first office buildings including the Corn Exchange were opened in about 1810.

Throughout the 19th century Liverpool's trade and its population continued to expanded rapidly. Growth in the cotton trade was accompanied by the development of strong trading links with India and the Far East following the ending of the East India Company's monopoly in 1813. Over 140 acres (0.57 km2) of new docks, with 10 miles (16 km) of quay space, were opened between 1824 and 1858.[3]

During the 1840s, Irish migrants began arriving by the thousands due to the Great Famine of 1845-1849. Almost 300,000 arrived in the year 1847 alone, and by 1851 approximately 25% of the city was Irish-born. The Irish influence is reflected in the unique place Liverpool occupies in UK and Irish political history, being the only place outside of Ireland to elect a member of parliament from the Irish Parliamentary Party to the British parliament in Westminster. T.P. O'Connor represented the constituency of Liverpool Scotland from 1885 to 1929.

As the town become a leading port of the British Empire, a number of major buildings were constructed, including St. George's Hall (1854), and Lime Street Station. The Grand National steeplechase was first run at Aintree in 1837.

Between 1851 and 1911, Liverpool attracted at least 20,000 people from Wales in each decade, peaking in the 1880s, and Welsh culture flourished. One of the first Welsh language journals, Yr Amserau, was founded in Liverpool by William Rees (Gwilym Hiraethog), and there were over 50 Welsh chapels in the city.[5]

When the American Civil War broke out Liverpool became a hotbed of intrigue. The last Confederate ship, the CSS Alabama, was built at Birkenhead on the Mersey and the CSS Shenandoah surrendered there (being the final surrender and end of the war).

Liverpool was granted city status in 1880, and the following year its university was established. By 1901, the city's population had grown to over 700,000, and its boundaries had expanded to include Kirkdale, Everton,[6] Walton, West Derby, Toxteth and Garston.[3]

20th century[edit]

1900-1938[edit]

During the first part of the 20th century Liverpool continued to expand, pulling in immigrants from Europe. In 1903 an International Exhibition took place in Edge Lane. In 1904, the building of theAnglican Cathedral began, and by 1916 the three Pier Head buildings, including the Liver Building, were complete. This period marked the pinnacle of Liverpool's economic success, when it regarded itself as the "second city" of the British Empire.[3] The formerly independent urban districts of Allerton, Childwall, Little Woolton and Much Woolton were added in 1913, and the parish ofSpeke added in 1932.[7]

Adolf Hitler's half-brother Alois and his Irish sister-in-law Bridget Dowling are known to have lived in Upper Stanhope Street in the 1910s. Bridget's alleged memoirs, which surfaced in the 1970s, said that Adolf stayed with them in 1912-13, although this is much disputed as many believe the memoirs to be a forgery.[8][9]

The maiden voyage of Titanic was originally planned to depart from Liverpool, as Liverpool was its port of registration and the home of owners White Star Line. However, it was changed to depart from Southampton instead.

Aside from the large Irish community in Liverpool, there were other pockets of cultural diversity. The area of Gerard, Hunter, Lionel and Whale streets, off Scotland Road, was referred to as Little Italy. Inspired by an old Venetian custom, Liverpool was 'married to the sea' in September 1928. Liverpool was also home to a large Welsh population, and was sometimes referred to as the Capital of North Wales. In 1884, 1900 and 1929, Eisteddfods were held in Liverpool. The population of the city peaked at over 850,000 in the 1930s.

Economic changes began in the first part of the 20th century, as falls in world demand for the North West's traditional export commodities contributed to stagnation and decline in the city. Unemployment was well above the national average as early as the 1920s, and the city became known nationally for its occasionally violent religious sectarianism.[3]

1939-1945: World War II[edit]

Main article: Liverpool Blitz

During World War II, Liverpool was the control centre for the Battle of the Atlantic. There were eighty air-raids on Merseyside, with an especially concentrated series of raids in May 1941 which interrupted operations at the docks for almost a week. Although 'only' 2,500 people were killed,[10] almost half the homes in the metropolitan area sustained some damage and 11,000 were totally destroyed. Over 70,000 people were made homeless.[3] John Lennon, one of the founding members of The Beatles, was born in Liverpool during an air-raid on 9 October 1940.

1946-1979[edit]

Significant rebuilding followed the war, including massive housing estates and the Seaforth Dock, the largest dock project in Britain. However, the city has been suffering since the 1950s with the loss of numerous employers. By 1985 the population had fallen to 460,000. Declines in manufacturing and dock activity struck the city particularly hard.

In 1955, the Labour Party, led locally by Jack and Bessie Braddock, came to power in the City Council for the first time.

In 1956, a private bill sponsored by Liverpool City Council was brought before Parliament to develop a water reservoir from the Tryweryn Valley. The development would include the flooding of Capel Celyn. By obtaining authority via an Act of Parliament, Liverpool City Council would not require planning consent from the relevant Welsh Local Authorities. This, together with the fact that the village was one of the last Welsh-only speaking communities, ensured that the proposals became deeply controversial. Thirty five out of thirty six Welsh Members of Parliament (MPs) opposed the bill (the other did not vote), but in 1957 it was passed. The members of the community waged an eight-year effort, ultimately unsuccessful, to prevent the destruction of their homes, which finally occurred in 1965. The incident led to a massive rise in Welsh nationalism, and a year later, Gwynfor Evans of Plaid Cymruwon the party's first seat in the Carmathen by-election.

In the 1960s Liverpool became a centre of youth culture. The city produced the distinctive Merseybeat sound, and, most famously, The Beatles.

From the 1970s onwards Liverpool's docks and traditional manufacturing industries went into further sharp decline. The advent of containerisation meant that Liverpool's docks ceased to be a major local employer. In 1974, Liverpool became a metropolitan district within the newly created metropolitan county of Merseyside.

1980s[edit]

The 1980s saw Liverpool's fortunes sink to their lowest point. In the early 1980s unemployment rates in Liverpool were amongst the highest in the UK, an average of 12,000 people each year were leaving the city, and some 15% of its land was vacant or derelict.[3] In 1981 the infamous Toxteth Riotstook place, during which, for the first time in the UK outside Northern Ireland, tear gas was used by police against civilians. In the same year, the Tate and Lyle sugar works, previously a mainstay of the city's manufacturing economy, closed down. By 1985, unemployment in Liverpool exceeded 20%, almost double the national average.

Liverpool City Council was dominated by the far-left wing Militant group during the 1980s, under the de facto leadership of Derek Hatton (although Hatton was formally only Deputy Leader). The city council sank heavily into debt, as the City Council fought a campaign to prevent central government from reducing funding for local services. Ultimately this led to 49 of the City's Councillors being removed from office by the District Auditor for refusing to cut the budget, refusing to make good the deficit and forcing the City Council into virtual bankruptcy.

On 15 April 1989, 96 Liverpool F.C. fans (mostly from Liverpool and nearby communities) were fatally injured in the Hillsborough disaster at an FA Cup tie in Sheffield. This had a traumatic effect on people across the country, particularly in and around the city of Liverpool, and resulted in legally imposed changes in the way in which football fans have since been accommodated, including compulsory all-seater stadiums at all leading English clubs by the mid 1990s. Many clubs removed their perimeter fencing almost immediately after the tragedy, and such measures at football grounds in England have long since been banned.

In particular this led to strong feeling in Liverpool because it was widely reported in the media that the Liverpool fans were at fault. The Sun sparked particular controversy for publishing these allegations in an article four days after the disaster. Sales of the newspaper in Liverpool slumped and many newsagents refused to stock it. 25 years on, many people in the city still refuse to buy The Sun and a number of newsagents still refuse to sell it. There was further controversy surrounding the tragedy in March 1991 when a verdict of accidental death was recorded on the 95 people who had died at Hillsborough (the 96th victim did not die until 1993). It has since become clear that South Yorkshire Police made a range of mistakes at the game, though the senior officer in charge of the event retired soon after.

The success of Liverpool FC was some compensation for the city's economic misfortune during the 1970s and 1980s. The club, formed in 1892, had won five league titles by 1947, but enjoyed its first consistent run of success under the management of Bill Shankly between 1959 and 1974, winning a further three league titles as well as the club's first two FA Cups and its first European trophy in the shape of the UEFA Cup. Following Shankly's retirement, the club continued to dominate English football for nearly 20 years afterwards. By 1990, Liverpool FC had won more major trophies than any other English club - a total of 18 top division league titles, four FA Cups, four Football League Cups, four European Cups and two UEFA Cups.[11] The club's iconic red shirt had been worn by some of the biggest names in British sport of the 1970s and 1980s, including Kevin Keegan, Kenny Dalglish (who also served as manager from 1985 to 1991 and again from 2011 to 2012), Phil Neal, Ian Rush, Ian Callaghan and John Barnes. The club has yet to win another league title since, although it has since won a further three FA Cups, three League Cups, a UEFA Cup and a European Cup.[12]

Everton F.C., the city's other senior football club, also enjoyed a degree of success during the 1970s and 1980s. The club had enjoyed a consistent run of success during the interwar years and again in the 1960s, but after winning the league title in 1970 went 14 years without winning a major trophy. Then, in 1984, Everton won the FA Cup.[13] A league title win followed in 1985, along with the club's first European trophy - the European Cup Winners' Cup.[14] By 1986, the city's two clubs were firmly established as the leading club sides in England as Liverpool finished league champions and Everton runners-up, and the two sides also met for the FA Cup final, which Liverpool won 3-1. Everton have enjoyed an unbroken run in the top flight of English football since 1954, although their only major trophy since the league title in 1987 came in 1995 when they won the FA Cup.[15] Everton added another league title in 1987, with Liverpool finishing runners-up.[16]

Another all-Merseyside FA Cup final 1989 saw Liverpool beat Everton 3-2. This match was played just five weeks after the Hillsborough disaster.[17]

1990s[edit]

A similar outpouring of grief and shock occurred in 1993 when James Bulger was killed by two ten year-old boys, Jon Venables and Robert Thompson.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar